Batteries for Trolling Motors – Knowledge Matters, Part 2

David HuttonPalmetto Fly n Fish, March 2021

In part 1, we took a deep dive into the different types of batteries, how they work, and some benefits to each. If you're not subscribed and missed it, here's the link to it:

Batteries For Trolling Motors, Part 1

Now, in part 2, we will look at the

practical side of things to help you decide on the battery you should

have, and how to get the most from it.

-----------------------------------------

The number one concern people have with a trolling motor battery is

always the same:

“How

long can I run a motor out on the water?”

Some guys wanna

go all day, some don't. But everyone wants to know the answer to that

question.

To answer it, we have to know two things:

1. A battery's amperage hour rating

2. A motor's current draw, in amps.

Let

me say up front that trolling motor run-time is not a, "one-size fits all," kind of thing.

But you can approximate your potential run time,

and have a good idea of what you'll need to get you there.

A battery's amperage hour rating, abbreviated as amp/hour, or "Ah," is like the gas tank of a car. It basically describes how much current a battery can deliver over time.

For example, a 100 amp hour battery will last longer than a 55 amp hour battery.

To be a little more precise, a 100 amp hour battery can deliver 100 amps of current for 1 hour – thus the name, “amp hour.”

This ability to cover a range of current draw possibilities is what saves us.

There's a simple mathematical formula that covers this, in fact:

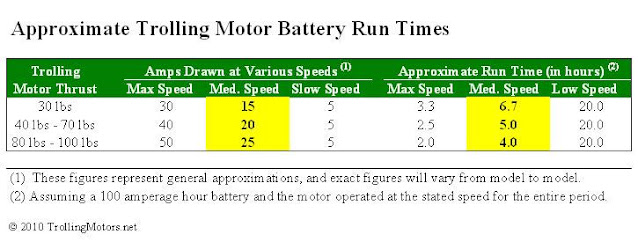

So, lets say your motor was running at a low speed, drawing 5 amps from your 100 Ah battery. Using the formula, we would divide 100/5 to get a 20 hour run time.

Going the other way, if you're running wide open and drawing 40 amps, the result would be 100/40, for a 2.5 hour run time.

Motor Current Draw

A motor's exact amperage draw rating isn't always easy to find, but it will be available from the manufacturer. You can check the spec sheet that came with the motor, or if you don't have that, check on the internet

Most manufacturers will only list a motor's maximum current draw at top speed. That's really all they can do, but it's enough.

With that information, we can extrapolate across the range, from zero to max, using that maximum value as a baseline.

But we don't run our motors at a constant speed for a defined time-span, do we?

We run them fast, slow, and an awful lot of the time, somewhere in between.

Sometimes we don't run them at all.

You have to understand that your power consumption is determined by the conditions, and how YOU choose to run the motor.

For example, if you must power through a high flow river current, or against a stiff wind, you will require a higher power setting and draw more current.

If you paddle protected backwaters a lot, as I do, you may draw very little current from the battery in a given fishing session.

So what's the simple answer to how much battery you need?

Drum roll please: There isn't one.

Take a look at the chart above, and notice the first word in the heading -

“approximate.”

Really, it all comes down to throttle

management. You can run at a moderate pace throughout the day, going

from spot to spot, using drifting, paddling, anchoring, etc., or, you

can run flat out for 2 1/2 hrs. and go to the other end of the lake.

But

the whole battery conundrum can usually be distilled down to:

Get

the physically largest deep cycle battery that you NEED, which

you can physically manage without throwing out your back, or upsetting the

balance of your boat.

This is different for each application.

For

trolling motor use in a small boat, for example, I generally recommend a battery with AT LEAST a

100 amperage hour rating, and a Group 24-31 case size rating.

In a kayak you may want a motor with a reduced thrust factor, and that could mean a smaller battery.

But

above all, know your motor's current draw and the battery's amp hour

rating.

From there, you can take what you've leaned here, do some

simple math and find out what you need for YOUR situation

And

that's a result!

Some Battery DO's and

DONT'S

Use

Variable Speed Motors

Using a variable speed motor (vs. a fixed speed motor) generally results in significantly longer run times. Variable motors are more energy efficient, especially at slower speeds. They are also much more convenient as they allow you to dial in the speed to the exact setting you want.

Actually, I'm not sure there are any fixed-speed motors available anymore. I haven't seen one, at least.

There are also new electronic devices

called “pulse width modulators” that feed the power to your motor

in high frequency pulses. This stretches out the battery life, and

they're worth considering if you want to add another tech project to

your system.

Use A Higher Voltage Motor

As

voltage increases, you can get the same power using less current. In

this way, larger

24v and 36v multi-battery trolling motor systems can provide the same thrust

as 12 volt motors with less current draw. This results in longer run

times.

The motors are more expensive, of course, and you need TWO or THREE batteries in series to pull off this trick, so

that might not be practical in YOUR situation.

But seriously long run times are possible with 24v or 36v motor.

Don't

Fully Deplete Your Battery: Big NO – NO!

Running

a

battery “bone dry” on a regular basis will reduce the lifespan of

your battery.

Whenever possible, make it a habit to recharge your

battery(s) before they are completely empty.

Using a battery voltage monitor while on the water will help you know your battery's charge

level, and reduce the chances of unexpectedly running out of juice

miles from shore.

For lithium batteries, use a lithium specific monitor that reads in remaining amp

hours, and not just voltage.

Remember Your Batteries In The Off-Season

It's

really bad for batteries to be left uncharged for months at a time. It contributes to shorter battery life and reduced performance.

During the off-season, use a battery tender or battery trickle

charger to keep a small amount of current running through your

batteries.

Alternatively, you can re-charge your batteries every

month or so to ensure they retain a charge and don't sit empty.

Both

options will significantly increase the life of your batteries.

Don't

Mix

Battery Types

Resist the urge to mix old batteries with new ones. Ideally you want

multi-battery banks to be of the same age and type.

Charge

Batteries After Each Use

Leaving

batteries in a discharged state after use will decrease their

longevity and performance. So make it part of your routine to charge

them as soon as possible after you've used them.

If you are using

flooded, wet-cell batteries, also get in the habit of checking and

topping up liquid levels every time you use them.

Storage

Keep your batteries in a cool, dry place in the off-season and

maintain them in a charged state.

Connecting the

Battery

- Terminal connectors should be periodically examined

for signs of corrosion. Don't just look at 'em, or pour Coca-Cola all over 'em...Take them apart and clean them as needed.

Know what's happening there, and keep ahead of any problems with your

connections.

- The best way to hook

the motor to the battery is with large-lug, ringed terminals that attach

flat to the terminal with nut and bolt hardware.

If your battery has tapered posts,

make sure they are clean and bulldog tight.

If you have alligator clip connectors, dump them as soon as possible.

From there, have an

in-line circuit breaker, and use quick disconnects on the motor and battery if you want to remove them.

- Your wiring should be sized

appropriately.

Wire that is too small will not conduct current

efficiently, and will dissipate power in the form of heat.

Wire that

is too large conducts current fine, but it may cost you more than is

needed.

Each motor manufacturer recommends the proper wire size,

depending on how far from the battery the motor is placed. Since

we're not tossing out random info, here, I'm gonna tell you to find

out what wire sizes your motor manufacturer says to use... and then

follow those instructions to the letter.

- Keep your battery

clean and covered in use, and don’t leave it outside to freeze over

winter.

To really be honest, these things are easily as important as the battery itself.

FAQ

Q.

What do the "group numbers" on batteries mean?

A. The group number

indicates case size

dimensions.

This is important because you could maybe use a

somewhat smaller battery, and still get the same capacity as a larger

one. That's why its important to understand the amp hour

specification and how it applies.

Q. Is one brand better

than another?

A. Generally speaking, no.

Saying that will get

many brand loyal people worked up, but it is ALWAYS your

first priority to understand that battery current capacity / Motor

current draw = run time.

The

name on the case, where you bought it, it’s price, or even its

internal makeup are secondary, and may mean next to nothing.

There

may be those batteries with better warranties, or some slight edge in

materials, and certainly there's some great advertising hype

involved.

But the science, technology and manufacturing behind

batteries is well established, and plenty of people get YEARS from

their Walmart brand batteries.

Q. Can batteries go bad from

sitting?

A. Absolutely.

They lose a percentage of their

charge, month after month, just sitting on the shelf. This means that

the manufacturing date is important at the time of purchase. Look for batteries that are no

more than 6-8 months old.

And once charged and in service, they

should not sit around without being on the charger periodically to

keep them topped up. I cycle charge those not in use once a month,

and I rotate them into service through the season.

Q. Are

these batteries expensive?

A. Yes.

However, it depends on your

financial situation.

Some guys think nothing of having $4500 tied up

in lithium batteries, high-end chargers, etc.

Me, that’s my

fishing budget for the rest of my life!

So it's a different

expense for everyone.

For those of us with pockets of average

depth, plan to spend $1-$1.75 per amp hour for a decent AGM, deep

cycle battery. You can shop around and find sales, or deals, but plan

on that.

TIP: You can link batteries in parallel to gain

current capacity.

For example, I

use TWO 55 amp hour batteries connected in parallel to give me 110

amp hours. I get them for free, so its a no brainer to use them.

As

you can see, when connected this way, the current capacity is

additive.

This means each time you add one to the circuit,

in parallel, you add the new battery's current to the total.

So

you could buy one, now, to get you going, and literally double or

triple your run time by buying another next month!

Q.

How often should I charge the battery, and do I need a special

charger?

A. That's easy: charge it as soon after discharging it,

as possible.

Ideally, when you get it home from using it, you'll

put it on the charger straight away.

As for the charger, use a

charger that offers self-adjusting current levels, and a maintenance

feature. This type reduces the amount of current flowing to the

battery as it gets approaches peak charge, and then it shifts to

“charge maintenance mode,” what some people call a “trickle

charge.”

Finally no matter how careful and knowledgeable

you are – things can go wrong.

Because of that, I strongly urge

you to have a collapsible paddle on board, just case.

For

general information about trolling motor batteries, this will

help:

www.trollingmotors.net%2F86992071-picking-a-trolling-motor-battery

Thanks to the following online resources for their presence and information...

Dakotalithium.com

trollingmotors.net

wikipedia

https://www.crownbattery.com

Interstatebatteries.com

battlebornbatteries.com

As always, thanks for reading, and dont forget to...

visit us on Facebook at: Palmetto Fly n Fish

Tight Lines,

David

Palmetto Fly n Fish

© All rights reserved, 2021